Robert (Producer & Percussionist)

This is an excerpt from his book, Gabrielle:

This is an excerpt from his book, Gabrielle:

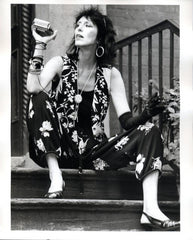

Because we used her name in the title of the band (who was going to buy music from Robert Ansell & The Mirrors?), many people thought Gabrielle was a musician. She wasn’t. She was a director. Always a director. I pulled the lead oar in the making of the music, but she was the guide and catalyst.

Almost all of our albums began with bottom drum tracks I put down, often with Sanga of the Valley or Gordy Ryan, often alone. I am a bottom drummer, the lowest in the musical food chain of the lowest in the musical food chain. Since I was at the bottom of the music, I realized that I should concentrate on the bottom of the people dancing in the room. Yup – I got the feet and Sanga got all the good parts. I must have been a podiatrist in my last life. Sanga tells a story about me that I’m not sure is true. “Did you see that gorgeous woman dancing in the room,” he supposedly asked me. “I’m not sure”, I supposedly said. “What did her feet look like?”

My job was to create the foundation of an energy that Gabrielle needed in the moment to help the dancers get to where she wanted to help them go. If some beats or patterns I made up worked, if they got people moving, I remembered and eventually recorded them. Actually, to be honest, I not only watched the feet, but also Gabrielle’s butt. For more than thirty years, I watched Gabrielle’s butt. That was the guide post. If that thing was moving, we were grooving. If it wasn’t, we weren’t. Simple!

Gabrielle and I built the songs from these butt-moving bottoms up, deciding what bass player to add to the drums, what vocalist, or violinist, etc. We managed to get astounding musicians to play with us, maybe because of the freedom we gave them, maybe because of the chance to work with Gabrielle. Her actual studio participation varied from album to album; for some, she was at most of the sessions; for some, she came when we needed her to get a specific performance from a musician; for some, she was only at the mixes. And, a lot of our work came outside the studio, at home, listening to the tracks and deciding how to bring them to the next level. She didn’t always know what would work, but she always knew what didn’t.

Rock ‘n’ roll was great, but Gabrielle’s spirit was more primitive and tribal. I guess I was responsible for our move to ambient music. Gabrielle loved to use live drums in her classes and workshops. In 1979 and ’80, she was teaching a weekly class in New York City, and I was playing drums with Gordy (a dear friend and member of the Baba Olatunji band) and an elderly (late ‘60’s) Cuban percussionist, Manuel, I had seen playing in Central Park. We were playing wonderful rhythms and the people were dancing intensely to them. I thought it would be a good idea to record the “bottoms” we were coming up with weekly. We added pitch instruments to them and they became our first major album, Totem, a (then) new style of music for dancing and ambience – no lyrics, no choruses, no verses – a rhythm ride. Great for dancing; great for making love. Gabrielle and I always did a test drive.

Rock ‘n’ roll was great, but Gabrielle’s spirit was more primitive and tribal. I guess I was responsible for our move to ambient music. Gabrielle loved to use live drums in her classes and workshops. In 1979 and ’80, she was teaching a weekly class in New York City, and I was playing drums with Gordy (a dear friend and member of the Baba Olatunji band) and an elderly (late ‘60’s) Cuban percussionist, Manuel, I had seen playing in Central Park. We were playing wonderful rhythms and the people were dancing intensely to them. I thought it would be a good idea to record the “bottoms” we were coming up with weekly. We added pitch instruments to them and they became our first major album, Totem, a (then) new style of music for dancing and ambience – no lyrics, no choruses, no verses – a rhythm ride. Great for dancing; great for making love. Gabrielle and I always did a test drive.

I was a little concerned at this session because Manuel would occasionally break into song when we were playing at the classes. He spoke almost no English. I can get by in Spanish, but not with anyone from Cuba; their speed and accent floor me. Before the engineer hit RECORD, I turned to Manuel and said “No cantele” or something like that. We were going three drummers at a time, money was tight and I didn’t want to waste a take. Sure enough, several minutes into the song, Manuel started singing. The engineer looked at me through the glass, but I shook my head so he would keep recording. It turned out great – in fact, we called the song La Cancion de Manuel. To this day, I’m not really sure what the words were. When we asked him, all we could get was that he was singing about the “ritual”. Gabrielle had been dancing in the control room while we were recording and he could see her through the glass.

Of course, after making this music, it was my job to sell it. Not an easy task. We were “bin-challenged.” There were very few bins in those days. We weren’t rock, we weren’t soul, we weren’t jazz, we weren’t classical, we weren’t pop. What to do? Gabrielle’s movement work was moving through this milieu called “New Age” and I thought I could get some distribution in that market which was just emerging. Not! It turned out that New Age music in those days was all harps, feathers, synthesizers and balloons. Our music had drums, and drums were not spiritual in the early ‘80’s. But we pushed on and, eventually our music found its way around the globe. And drums are now happening!

I had working titles for all of the songs as we went along with each album. None of them lasted. Gabrielle handled the titles for our songs, sometimes to capture the essence of a completed song, sometimes to guide the development of one. The album Bones is a good example. I had put down six bottoms, basic drums only and sent a cassette to Gabrielle who was teaching in Europe for a long stretch. A week later, we’re on the phone and she says: “Not sure what we’ll call this album, but bottom #3 should be a warm-up and we’ll make the other five songs in the rhythms, but call them by the name of animals. And she named the animals.” Hence, the album Bones, with its songs Dolphin (flowing), Raven (staccato), Snake (chaos), Deer (lyrical) and Wolf (stillness). And she pulled another one of her G-Strings for the song, Snake. We decided we wanted a violin over the drums. Gabrielle said it had to be a mournful violinist. Three days later, we walked into our favorite coffee shop and ran into our friend Boris, the Russian rock 'n' roll idol who we later made the albums Refuge and Bardo with. He was excited to introduce us to a new friend, Jonny Cunningham, at the next table. He happened to be a violin player in a popular rock band. A Scottish violin player. The archetypical mournful violin player.